“My name is Nand Kishore, and I’m a National para-athlete from Hyderabad, Telangana.

Nearly two years ago, on May 29th, 2023, my life turned upside down.

I was a marathon runner. A fitness enthusiast. I had just started my Master’s in Hospital Administration and was working as a personal assistant to one of the director at AIG Hospital in Gachibowli. Things were finally settling down.

That morning, I was riding my bike through the rain on Kishan Bagh Road. Due to ongoing road work, the road was muddy and uneven. My bike skidded and I fell towards the opposite side of the road with my bike and I was still on my bike. As I lay there, trying to grasp what just happened, a car from the opposite direction hit my bike. I was conscious, but I couldn’t feel my lower body. Right then, I knew something was terribly wrong.

I didn’t wait for help. I called the ambulance myself. The ride to the hospital, around 18 km away, felt like a lifetime. All I kept thinking was—don’t black out. If I do, I might not wake up.

At the hospital, the scans showed I had an L1 burst fracture. I was rushed into emergency surgery. Metal rods. Screws. Four hours under the knife. When I woke up, the doctors told me what no athlete wants to hear—“You may never walk again.”

I was broken. Not just physically—but in every possible way.

I thought of my father—we lost him in a bike accident when I was just 11. I thought of my brothers—we’re three siblings—and how one of them lost his leg in an accident while trying to visit Dad in the hospital. And now, it was me.

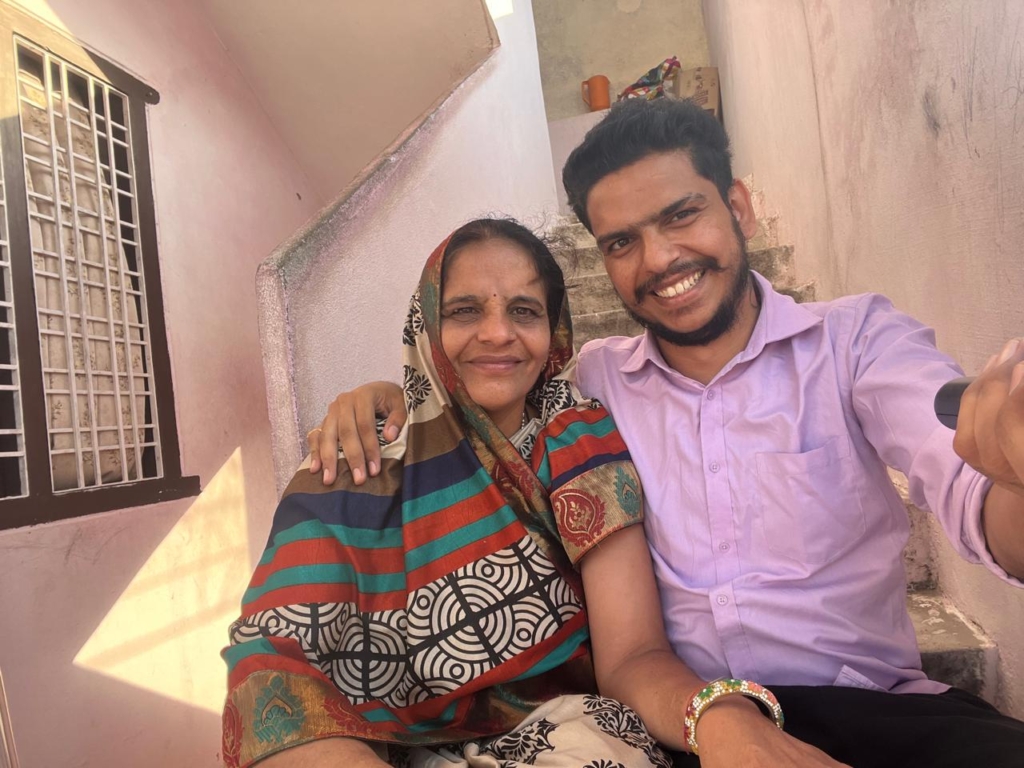

We didn’t tell our mother for a few days. She had been through enough already. After my father passed, she worked in people’s homes to feed us. At 14, I started working too. I went to school during the day and worked at a jewellery shop at night. My first salary was ₹1,200. Over the years, I did everything I could—worked at Reliance Fresh, sold products at Patanjali, worked at RTA mobile pollution van, worked many other things for commission, managed marathon events, taught tuition.

Academics weren’t easy for me. I had 28 backlogs, but I didn’t give up. I cleared them all and completed my degree. After that, I worked at Niloufer Hospital for two and half years, in Udai Omni Hospital for 18 months before getting the opportunity at AIG.

I had also enrolled in a Master’s in Hospital Administration. For the first time, life was finally coming together.

And then, this accident happened.

The initial days after surgery were tough. I couldn’t sit, stand, or move without help. But something inside me kept saying—”You’re not done.” I started by making YouTube videos—not to inspire others, but to motivate myself. Slowly, I learned to sit again. Then stand with support. Then walk with a walker. Then climb a few steps. The road wasn’t smooth—I went through multiple infections, bedsores, and follow-up surgeries. The physical pain was one thing—but seeing my mother slip into depression when I returned to work was the hardest part.

That’s when I found wheelchair racing. I reached out to the Paralympic Committee of India and they told me I had the right build for the sport. But it wasn’t easy. A proper racing wheelchair costs over ₹10 lakhs. There are no Indian brands, and no support for para-athletes like us in Telangana. I borrowed a 7 years old used racing chair worth ₹1 lakh and trained with it for just 45 days.

Then, I raced at the Nationals. I came fifth. I was the first wheelchair racer from Telangana.

In March 2025, at the Khelo India Para Games, I shaved 8.5 seconds off my 800m time, and 20 seconds in 1500m despite using outdated equipment. That performance got noticed. One day, India’s top female wheelchair racer, Kiran Shriram Metkar, called me. She said, “You have what it takes to win gold in 2026 nationals.”

That moment changed everything. I quit my job. This is my path now.

I now train on broken synthetic tracks at Osmania University. I reach out to NGOs, talk to my old colleagues at AIG, and knock on every door I can. I’m not asking for money. I’m asking for a chance—a proper chair, access to coaching, and support to represent India.

My goal is to compete internationally. My dream is to bring home a medal for India at the 2028 Paralympics. I also want to work on creating better support systems for para-athletes—especially in states like ours, where we’re still far behind in facilities and recognition.

My mother, who once seemed broken by life, now watches me race with pride. My brothers stand by me in every step of this journey.

I’m not just racing for myself. I’m racing for everyone who’s ever been told, “This is the end.”

To anyone out there going through the worst—you’re stronger than you think.”